The USA may be missing from the Rugby World Cup in France later this year. However their domestic scene is thriving with yet another new winner of Major League Rugby in the shape of the New England Free Jacks. Driven by a great first phase attack, and reinforced by a physical defence the Free Jacks secured their first MLR shield.

Building a Dominant Defence

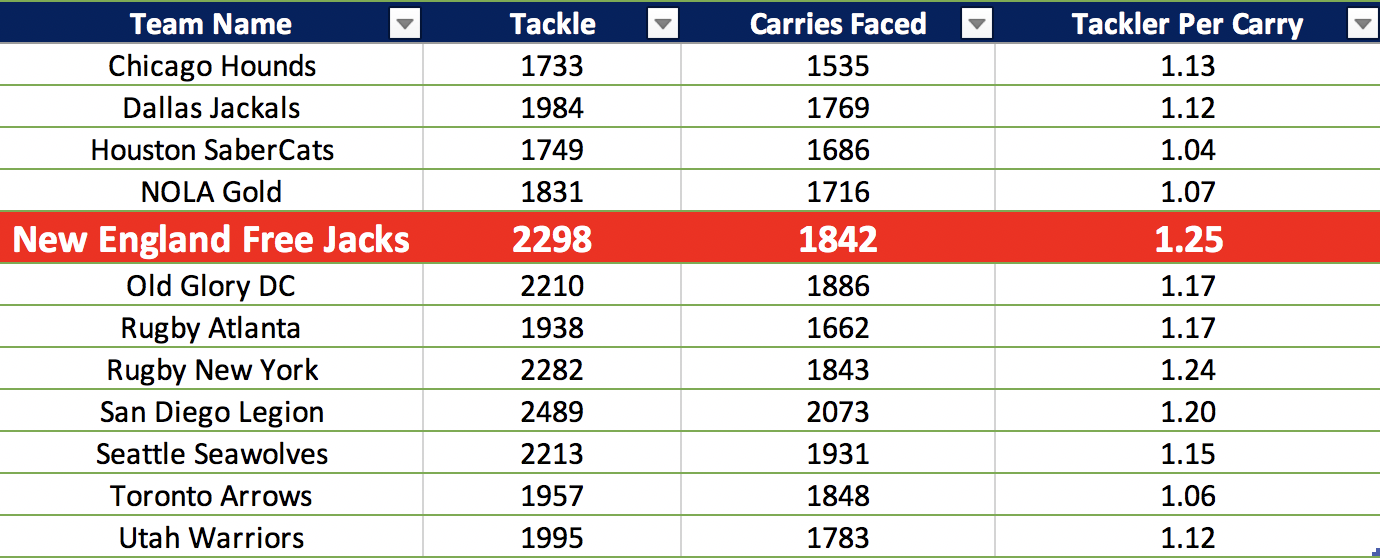

While attack is great, the main driver of New England’s success was a league leading defence. The New England defence was characterised by their use of double tackles. We can see this using data from Oval Insights by looking at the total tackles they make per opposition carry. In the MLR, New England led the way with a ratio of 1.25 tacklers per carry.

This double tackle system allowed the Free Jacks to really dominate their opponents physically. The second tackle from their semi final against Old Glory DC really set the tone and showed New England’s defensive DNA.

Line Speed and Double Tackles: The Pillars of New England’s Defence

New England’s defence starts with strong line speed pressing hard off the line to close down the Old Glory attack. Both tacklers hit high on the body but still win the shoulder battle against the ball carrier. When they first make contact they are able to absorb the force but remain on their feet and then drive through to complete the tackle.

The follow up phase is no different from New England. The Free Jacks set their width well and they look to pressure the attacking players. The initial pressure is square off the line meaning the defence takes as much ground as possible on the attack before a strong double tackle stops any forward momentum. All this results in another phase for Old Glory which finishes behind the gainline.

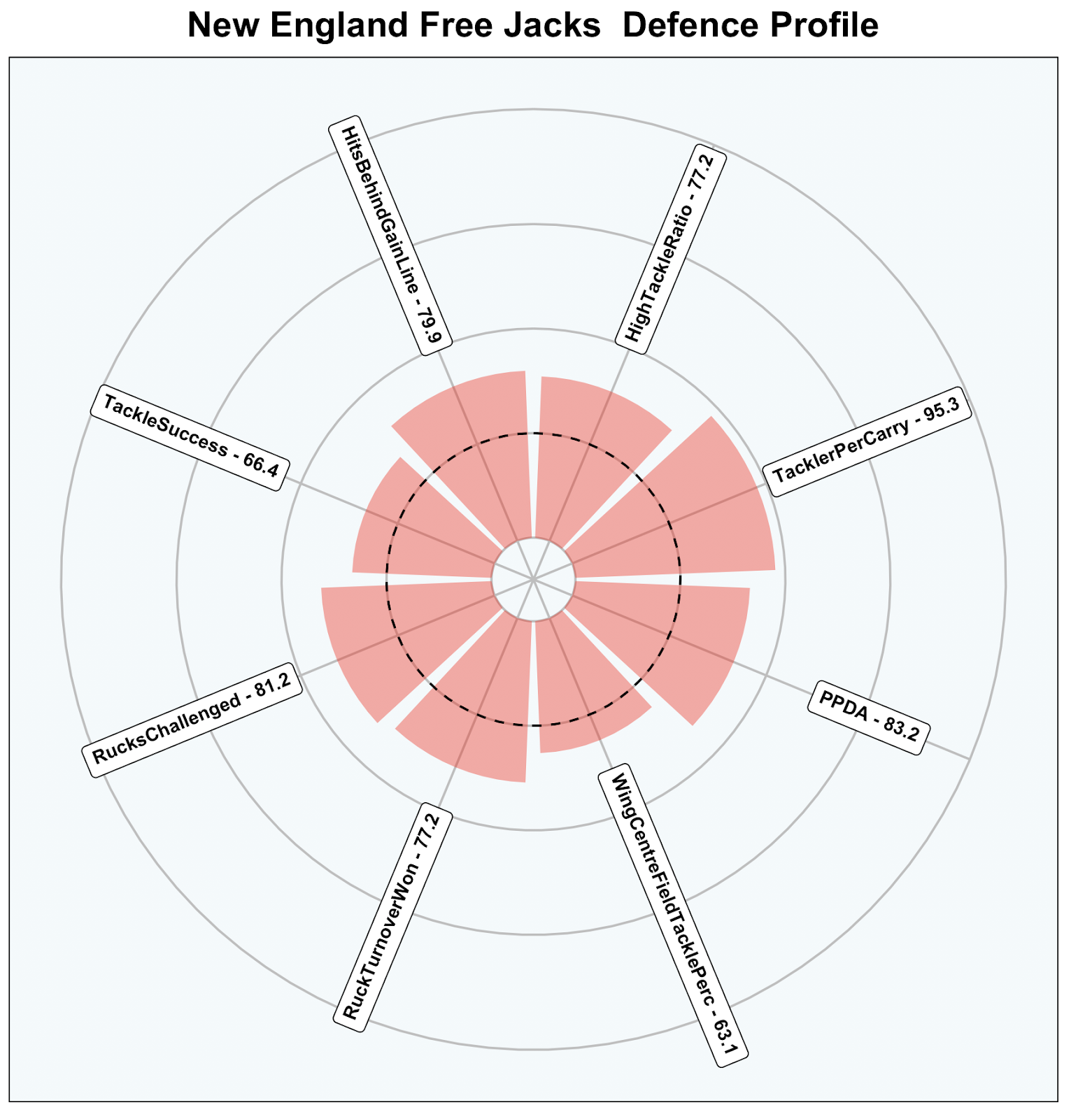

This impressive line speed is shown in the Free Jacks defensive radar. They were above average for tackles behind the gainline as well as sitting in the top 20% of sides for line speed – measured from Pass Per Defensive Action. It was this constant line speed that set the Free Jacks apart and allowed them to impose themselves on the opposition even when they didn’t have the ball.

Turnovers: The Final Pillar

The other key part of their defence was their ability to turnover the ball as we saw above the Free Jacks claimed more turnovers than 75% of sides while they also sat in the top 20% for rucks challenged.

This steal against Houston shows how their physicality opened the chance to win turnovers. A strong double tackle stops any momentum for the ball carrier. This also means the two clearing players end up going beyond the ball opening the window for the turnover.

This turnover against Chicago shows similar skill. A great initial press means that they make the tackle well behind the gain line. Then a great low tackle means the carrier can’t get his legs pumping through the contact. Semisi Paea shows great skills to control the ball carrier’s fall before then snaffling the ball and winning a turnover.

Scramble Mode: Free Jacks Defensive Resilience

However sometimes even the best defences are broken and occasionally you need to engage scramble mode. One of the benefits of the New England defence is there super aggressive press means most of the breaks occur outwide. This limits a breaking player’s option and means the cover can work towards a touchline.

Or take this incredible cover tackle from full back Reece Macdonald. The 15 is another Kiwi import for Free Jacks and you can see why they recruited the Bay of Plenty player as he makes a wonderful last ditch tackle.

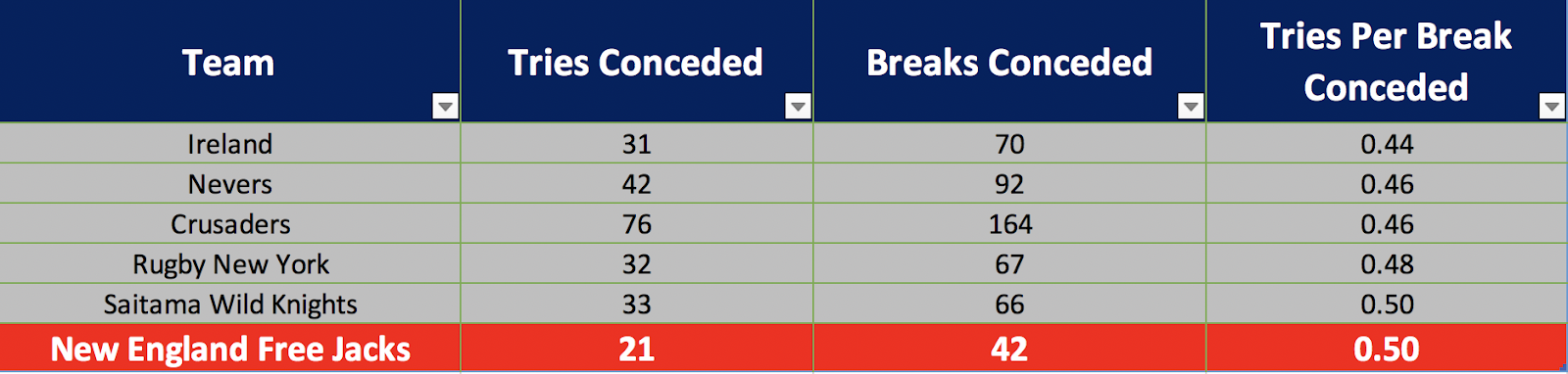

By limiting the amount of the breaks they conceded down the centre of the field alongside amazing defensive efforts meant that New England maintained a low tries per break ratio. Their tally of 0.5 tries per break was beaten by the Rugby New York Iron Workers yet conceded 20 fewer breaks. However their scramble can be appreciated even more in a global sense as they sat joint 5th overall.

Unleashing the Attack: New England’s Offensive Prowess

However while defence was the main driver of New England’s success it is only half of the game. The side from Quincy also brought an incredible attack which looked to spread the ball and led to the Free Jacks scoring 606 points, a total only beaten by the 610 points from San Diego Legion.

First Phase Mastery: Unravelling Opponents with Precision

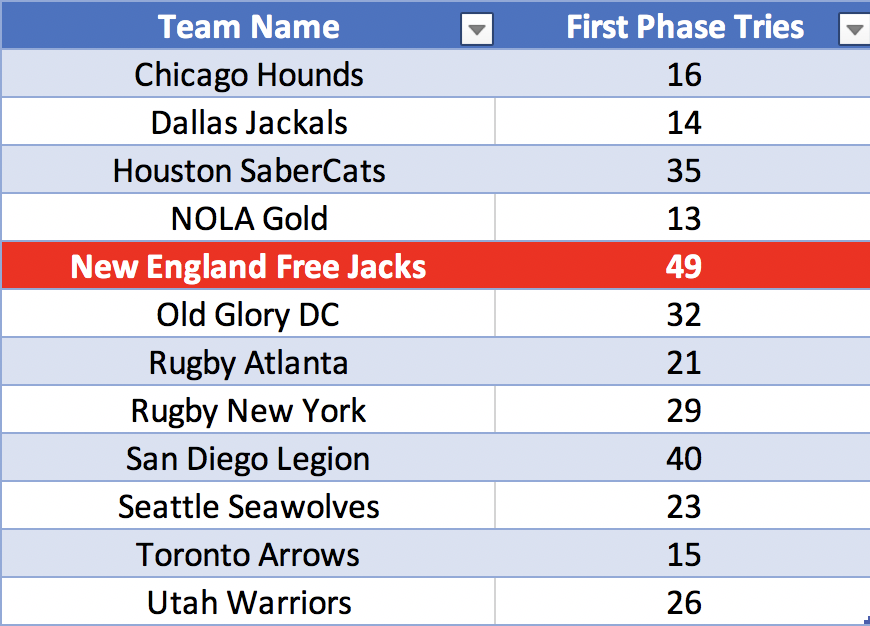

This dominant attack was underpinned by an ability to score first phase tries. The Free Jacks scored 49 first phase tries across MLR 2023, 9 more than second best San Diego Legion and over 3x as many as the lowest side NOLA Gold.

Take this try from their game versus Toronto Arrows. It starts from a lineout just inside their own half and Scott Mathie’s team look to spread the ball immediately. The play is built off having multiple layers to fix the defence.

The first layer is built around Fly Half Potroz. The New Zealand born Potroroz has an option both on his outside and inside which helps pin the initial defenders. He gives the pass early to his third, pull back, option. This allows Le Roux Malan to square his opposite number before unleashing the second pod.

The second pod has the same set up as the first. This play is designed to fix the widest Toronto defender. The final pull back option (pink) is able to drift out on the pass meaning Le Sage is able to evade the final defender. The end result is a superb try which helped show the dominance of New England.

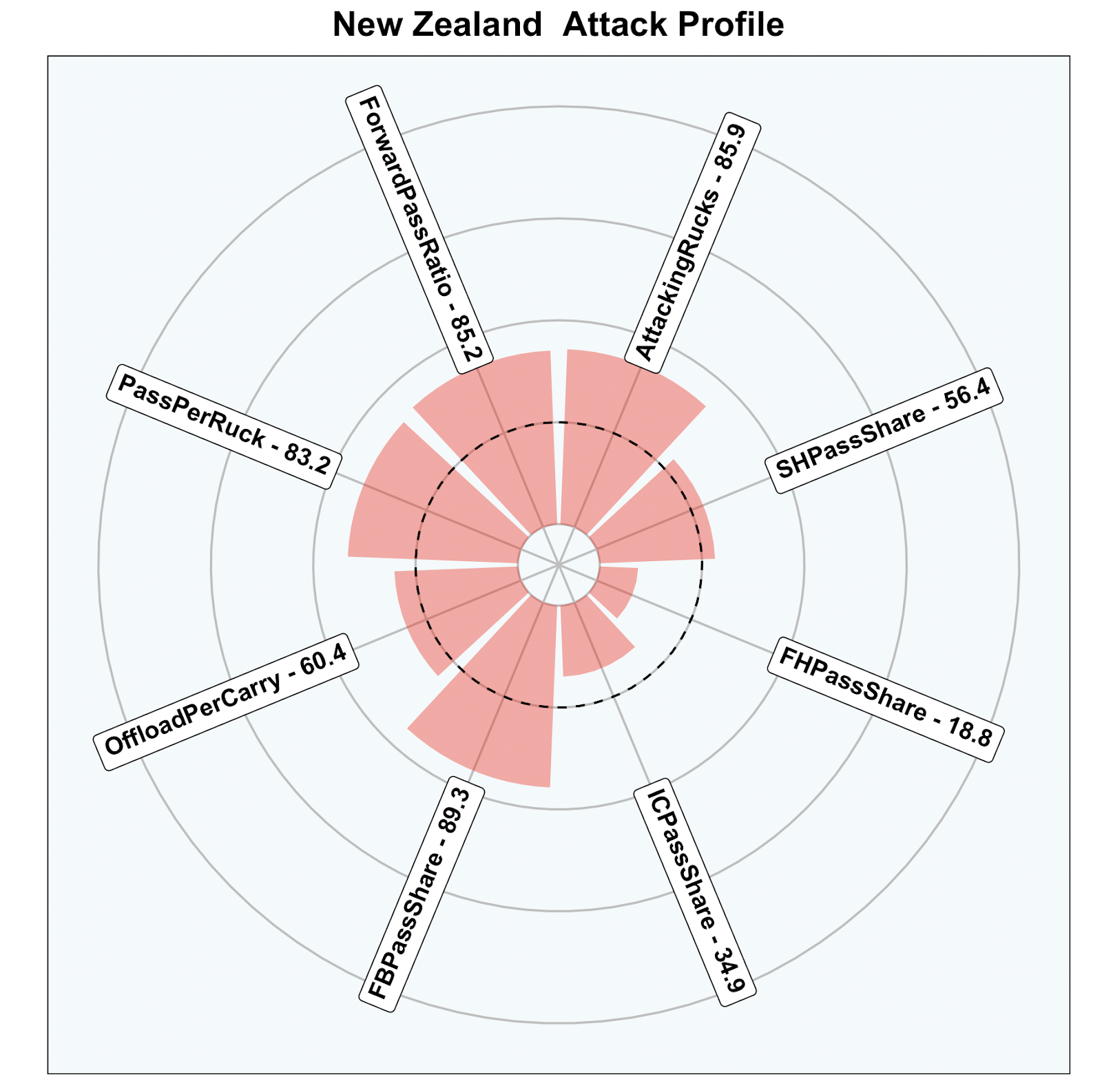

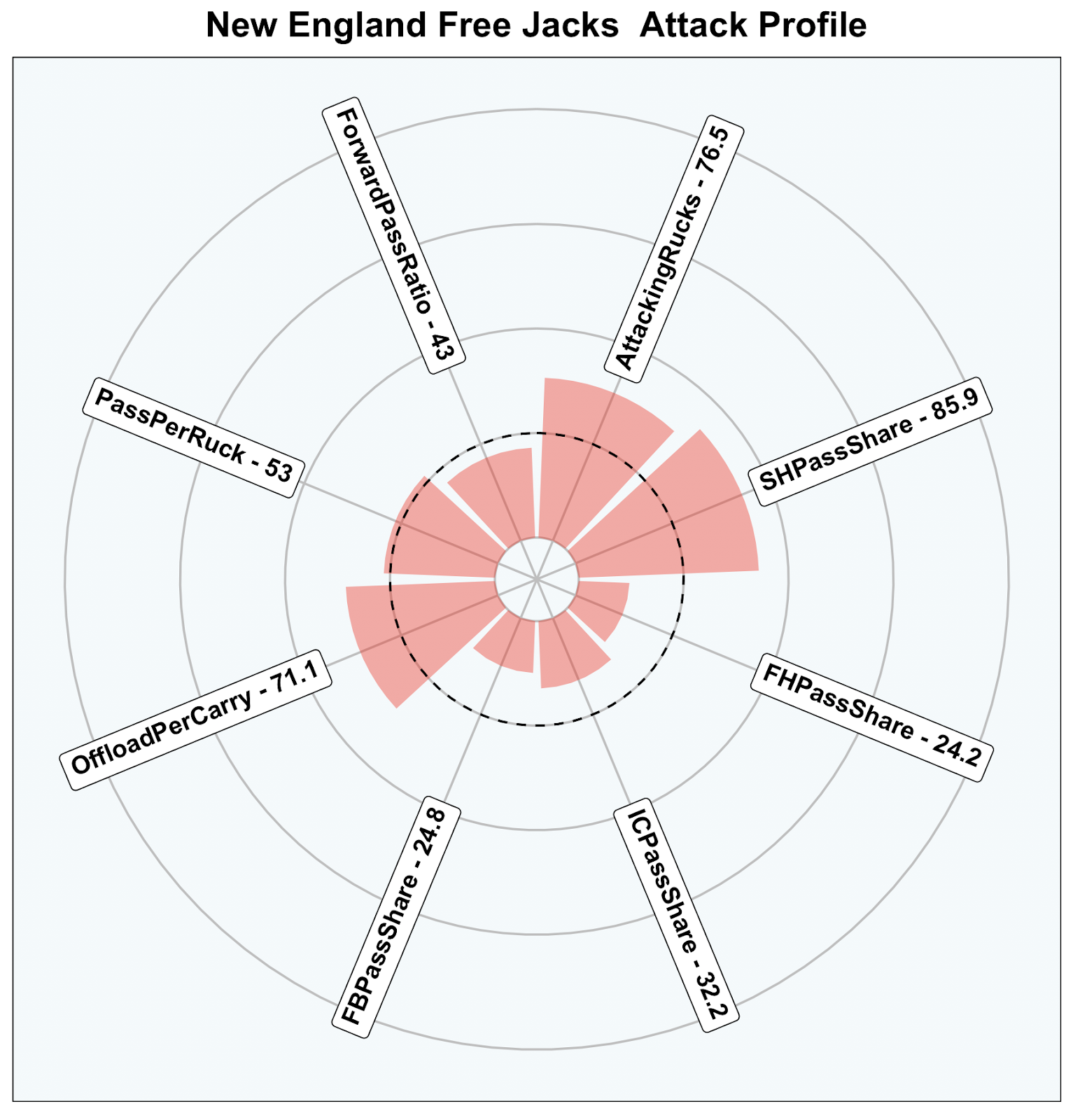

Using Oval Insights data we can also look at how New England looked to attack sides. For starters we can see how reliant they are on their scrum half as the driver of their attack, with the 9 making a higher share of passes than 85% of professional scrum halves in world rugby.

Kick Return Brilliance: Transitioning with Speed and Precision

One other key part of the Free Jacks attack is their ability on transition and particularly kick return. On kick return they were often able to beat first up defenders and get back on the front foot allowing less time to recover for the opposition.

Take this clip from the final, Jason Potroz receives the ball right on the touchline. Normally this is a difficult place to escape but the Fly Half attacks into centre field and beats a defender. The Kiwi is then able to free his hands and offload. The momentum is clearly with the Free Jacks forcing Ma’a Nonu to kill the ball. The resulting penalty extends the Free Jacks lead to 6 points.

This example from the early season match versus Old Glory DC is also a great example of how they identified the space on kick return.

Reece MacDonald collects the bouncing ball and heads in midfield on return. This gives a chance for Free Jack players to regroup after a hectic few seconds.

The carry also has the added benefit of splitting the field which adds stress to the Old Glory defence. The Old Glory defence also doesn’t do a good job of re-aligning following the carry with just 4 players covering the blindside.

Potroz notices this and swings round from the left hand side to collect a pull back play from the New England forward pod. You’ll notice the pod doesn’t attack with the ball instead just pivoting, however it doesn;t matter as Old Glory over press the ball and Potroz’s run creates a four on two outwide. Potroz makes sure to engage the defence and passes the ball to free the outside attackers.

The chance is finished off well by New England though they need a little luck with a couple of players getting tangled which removes the drift defence. The finish once they make the initial break down the tramlines is superb. The show and go by Wian Conradie means that he can attack the inside shoulder. The number 8 then floats a ball inside to beat the full back to a hard working John Poland who gets a second touch and dots the ball down. A terrific transition try.

A Deserved Triumph: New England’s Journey to the MLR Shield

New England’s title exploits were built on a strong defence first and foremost. Their charge to the top defence in the MLR was built primarily on physicality in the tackle. To achieve this they tried to use double tackles aiming to out muscle and drive back the opposition ball carrier. Their stellar attack was built off an incredible first phase launch which delivered 49 tries. The attack was boosted by their ability on transition from kick return. The Free Jacks were a formidable outfit and they received a deserved first title. Given the strong foundations they have put in place this year they could become the second side to successfully defend the MLR Shield.